Snow Country Prison

Japanese American Internment Memorial

United Tribes Technical College, Bismarck, North Dakota

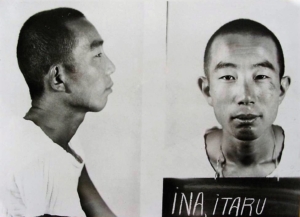

Ikusa hate-shi

Nao yukiguni no

Nao yukiguni no

The war has ended

but I’m still in

The snow country prison

— Itaru Ina, prisoner at Bismarck, ca. 1945

Internment Memorial Project

During World War Two, 125,284 men, women, and children of Japanese descent were subjected to years of unjust confinement in prison camps across the United States. One of the camps was a military post at Bismarck, North Dakota, known as Fort Lincoln.

Underway now at this unfamiliar location on the northern Great Plains is the “Snow Country Prison” memorial project, aimed at bringing some healing to the troubling wartime treatment of Japanese and Japanese American civilians.

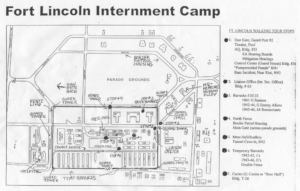

Today, the former Fort Lincoln Internment Camp is the campus of United Tribes Technical College (UTTC). College administrators and staff have joined with Japanese Americans (including descendants of former internees) to create a memorial on campus to recognize and honor more than 1,100 Issei (first-generation) and 750 Nisei (second-generation American citizens) who were incarcerated at the camp.

Little Known Role of Fort Lincoln

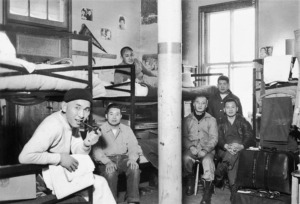

Fort Lincoln was originally constructed during the first decade of the twentieth century. In 1941, it was converted into a U.S. Department of Justice detention facility for the confinement of non-combatant men. First imprisoned behind 10-foot-high fences with guard towers were German merchant seamen and German nationals. In 1942, Issei immigrant community leaders on the West Coast were forcibly separated from their families and removed to the isolation and cold of North Dakota. In 1945, Nisei resisters from Tule Lake Segregation Center in northern California were similarly transferred to what eventually became known as “Snow Country Prison.”

On a government-issued questionnaire, more than 10% of imprisoned Japanese Americans refused to answer, qualified their answers, or defiantly answered “no” to two so-called loyalty questions. The questions sowed division and distrust, forcing an impossible and dehumanizing choice upon Japanese Americans. The “no-nos” were viewed as disloyal troublemakers, and hundreds were imprisoned in the stockade. Government repression and duress led thousands of disaffected Japanese Americans at Tule Lake to renounce their U.S. citizenship, enabling the Department of Justice to legally intern and deport them as “enemy aliens.”

These Japanese-American protesters had been demonized by government propaganda and racist stereotypes. The government suppressed knowledge about an unconstitutional strategy that was knowingly used to denationalize and deport the dissidents. There is little awareness about this chapter of the Japanese internment and the role played by Fort Lincoln Internment Camp.

* Bismarck’s Fort Lincoln is often confused with the first Fort Abraham Lincoln in the area that was decommissioned in 1891. That site is a now a state park located south of Mandan, North Dakota, on the west side of the Missouri River.

** UTTC is a tribal college owned and operated by the five federally recognized indigenous nations in North Dakota: Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate, Spirit Lake Tribe, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, Three Affiliated Tribes of the Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara Nation, and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians.

“This is important work, to not only recognize what happened to our Japanese American relatives, but to ourselves. This memorial will show that we’re still here, that we’ve survived and that now we need to move ahead.”

— Dr. Leander McDonald, UTTC President

Opportunity in the Making

The Snow Country Prison Japanese American Internment Memorial is an opportunity to highlight a story about resistance to oppression and raise up the memory of those who suffered incarceration for their stand as citizens.

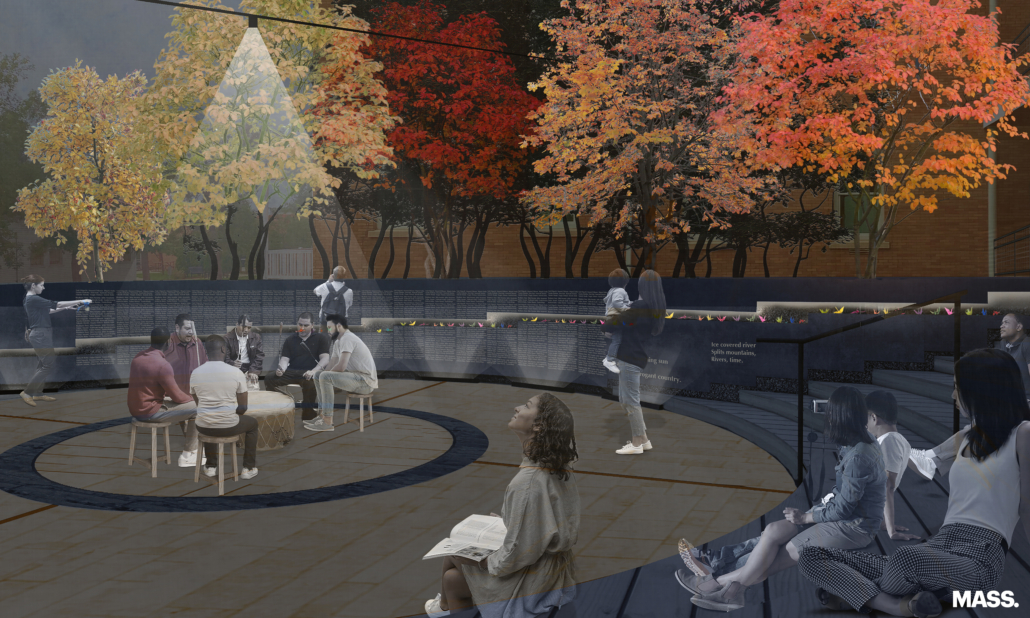

The “no-no’s” represent the essence of ganbatte, demonstrating steadfastness and unity. They challenged the United States government to hold true to its democratic ideals. This spirit aligns with the persistence of Tribal People, who have been similarly challenged throughout history. For more than 40 years, former internees and their relatives have visited UTTC to reflect on the little-known history of what happened there. With guidance and support from the tribal college, Japanese and Japanese-American visitors have been welcomed to tour the site, share their stories, and participate in ceremonies, finding moments of healing in the enriched setting of learning and hope.

The purpose of this memorial is to honor the legacy of Japanese Americans who were interned at Fort Lincoln and to help educate future generations. Through education, empathy building, and gathering together, the memorial promises to catalyze a broader reconciliation process around intersectional patterns of racial oppression and violence. It can serve as a model for other former camps around the country as planners search for healing through the use of acknowledgment and memorialization.

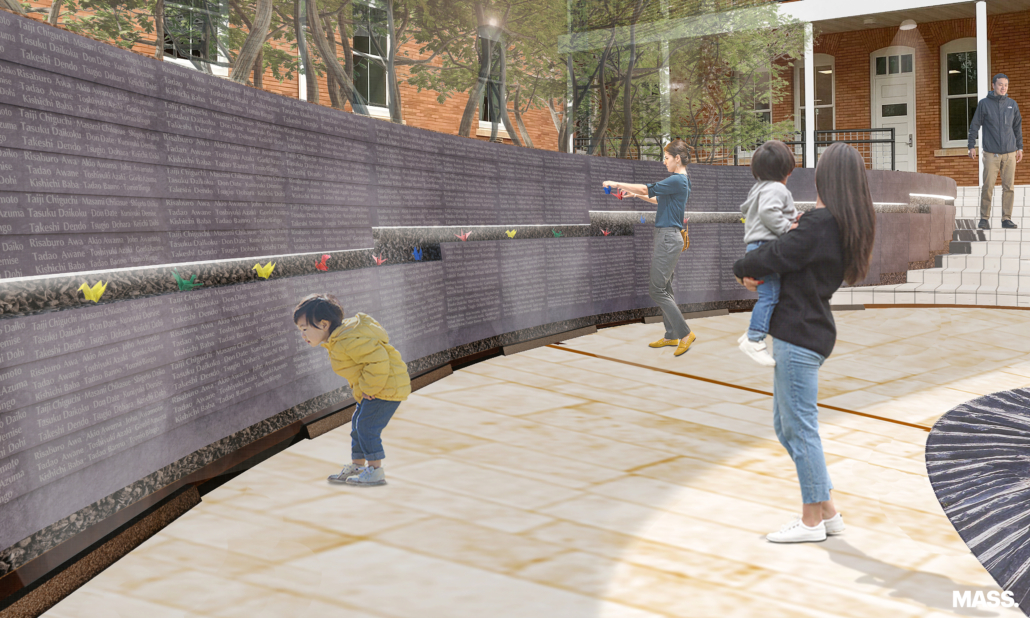

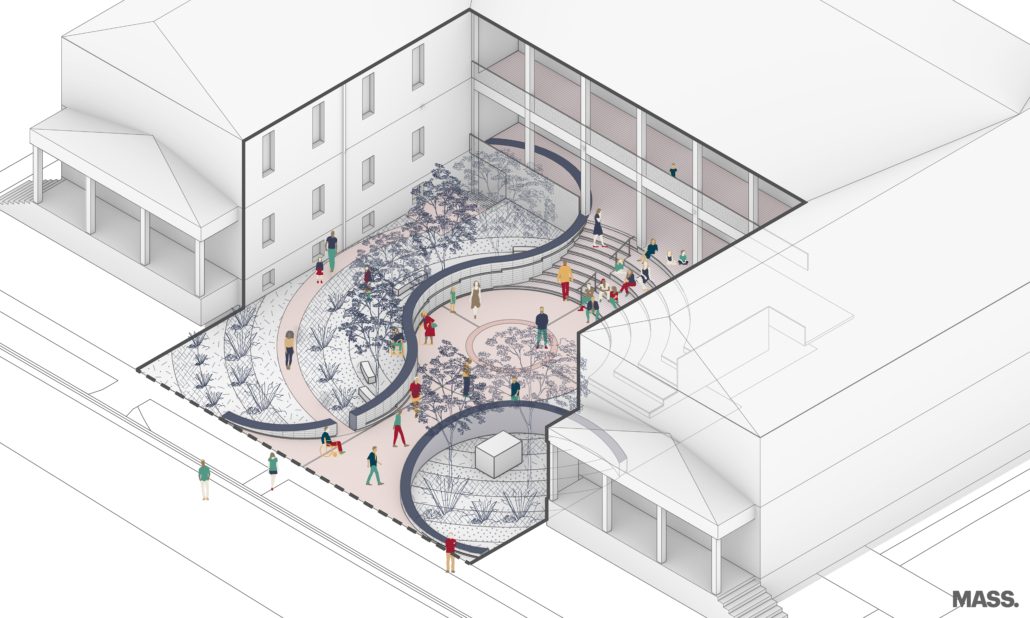

The Design

The design takes its cue from the craft of kintsugi, a process used in Japanese ceramics to mend broken pottery. A memorial wall will incorporate kintsugi as a gesture representing the bonding of cultures, communities, and individuals at a shared ceremonial space that honors the spirit of ganbatte (endurance and solidarity) exemplified by Japanese American and Native American resilience. Amphitheater seating in the courtyard will spill out from the veranda to provide gathering space and opportunities to connect to exhibitions inside and the campus cultural trail. This memorial, the first of its kind to acknowledge solidarity between Native and Japanese American communities, is slated to catalyze a broader reconciliation process around intersecting systems of oppression in America.

Design Highlights:

- Multi-Modal Access | The memorial’s design must accommodate flows to, through, and around this focal point in service of the site’s active use as a center for education.

- Kintsugi Memorial Walls | Kintsugi appears through the memorial’s wall, as a visible stitch across the site and as a receptacle for the tsuru (paper crane) offerings that brings healing and wholeness to the space over time. The walls are made of slate roofing tiles, reclaimed from the former prison’s roof.

- 4-Directions Drum Circle | A singular focal point centers the ceremonial functions of the place. The activation of this space reverberates across the memorial.

- Healing Garden | The energy of the ceremonial circle reverberates through the landscape, providing opportunities for growing significant Japanese and native plants, and for solitary reflection.

MASS Design Group: The Designers

MASS (Model of Architecture Serving Society) Design Group has partnered with the United Tribes Technical College and members of the Japanese-American community to create a unique intersectional social justice monument.

An internationally renowned design firm with representation across 20 countries, their highly acclaimed National Memorial for Peace and Justice (Montgomery, Alabama, USA) is changing the experience of who and what we memorialize in America.

The Stewards

This project would not be possible without the generous contributions and efforts from:

Major Funders:

Japanese American Confinement Sites Grant Program, National Park Service

United Tribes Technical College

MASS Design Group

Memorial Committee:

Satsuki Ina, descendant of Bismarck internee

David Koda, descendant of Bismarck internee

Brian Niiya, Densho

Barbara Takei, Tule Lake Committee

Duncan Ryuken Williams, University of Southern California

Leander McDonald, President, UTTC

Brent Kleinjan, UTTC

Dennis J. Neumann, UTTC

Melvin Miner, UTTC

Joseph Kunkel, MASS Design Group

Jeffrey Yasuo Mansfield, MASS Design Group

Mayrah Udvardi, MASS Design Group

Architectural Design Partners:

MASS Design Group

Website/Social Media:

Tamiko Nimura, Tule Lake Committee

Four Japanese words underpin the conceptual depth of this memorial’s design. We invite our partners to support the realization of this memorial and join one of the following donor circles:

|

Word |

Meaning |

Supporter Circle |

| Ganbatte | endurance and solidarity amidst attempts at division. | >$50,000 |

| Kintsugi | a Japanese ceremonial act of rejoining pottery; it has come to symbolize resilience and unification. | $20,001-$50,000 |

| Tomodachi | the Japanese word for friends. | $1,000-$20,000 |

| Tsuru | paper cranes; family members often leave them at internment and concentration camp sites. | <$1,000 |

Media Coverage

KFYR – Snow Country Prison Japanese American Memorial being built at United Tribes Technical College

Barbara Takei, “Internment Stigma,” (Discover Nikkei, 2012)

This project received the 2022 AIA NM Innovation Award and the 2022 AIA Santa Fe Unbuilt Design Award.

Contact

Courtney Lawrence

College Relations Director

United Tribes Technical College

(701) 221 1491